Last week, two more Periodic Review Boards took place — the 48th and 49th — for the last Russian prisoner held at Guantánamo, Ravil Mingazov, and for Ghassan al-Sharbi, a Saudi. Both men were seized in Faisalabad on March 28, 2002, on the day that Abu Zubaydah, regarded as a “high-value detainee,” was seized. The CIA’s post-9/11 torture program was initially developed for Zubaydah, who was regarded as a senior figure in Al-Qaeda, even though it has since become apparent that he was not a member of Al-Qaeda, and had no prior knowledge of the 9/11 attacks.

Last week, two more Periodic Review Boards took place — the 48th and 49th — for the last Russian prisoner held at Guantánamo, Ravil Mingazov, and for Ghassan al-Sharbi, a Saudi. Both men were seized in Faisalabad on March 28, 2002, on the day that Abu Zubaydah, regarded as a “high-value detainee,” was seized. The CIA’s post-9/11 torture program was initially developed for Zubaydah, who was regarded as a senior figure in Al-Qaeda, even though it has since become apparent that he was not a member of Al-Qaeda, and had no prior knowledge of the 9/11 attacks.

Nevertheless, Abu Zubaydah remains hidden in Guantánamo, still not charged with a crime, and those seized on the same night as him — either in the same house, or in another house that the US government has worked hard to associate with him — have faced an uphill struggle trying to convince the authorities that they are not of any particular significance, and that it is safe for them to be released.

In May, three men seized in the house with Abu Zubaydah, Jabran Al Qahtani (ISN 696), a Saudi, Saeed Bakhouche aka Abdelrazak Ali (ISN 685), an Algerian, and Sufyian Barhoumi (ISN 694), another Algerian, all had reviews, although no decisions have yet been taken about whether or not they should be released. Ghassan al-Sharbi (ISN 682) is another of the men seized with Zubaydah, and his review took place last Thursday (June 23), although he did not attend this hearing, or cooperate with the military personnel assigned to help him prepare for it, so it is certain that he will not be approved for release.

Whether rightly or wrongly, the PRBs function like parole boards (although, of course, the men in question have never been tried, let alone convicted of a crime or sentenced), and as such they require prisoners to show contrition and to persuade the board that they do not hold a grudge against the US, and will embark on peaceful and constructive lives if freed. To date, 24 prisoners have succeeded in persuading the boards to approve their release, while 12 others have failed. 15 decisions have not yet been taken, and 18 other men are awaiting reviews, which the Obama administration has promised will take place before President Obama leaves office.

Ravil Mingazov’s Periodic Review Board

I will discuss al-Sharbi’s case below, but first I want to look at the case of Ravil Mingazov (ISN 702), the Russian who was seized in another house in Faisalabad, the “Issa House,” that the US has tried — largely without success — to portray as a house associated with Al-Qaeda. It appears to have held many students who ended up in Guantánamo, as a US judge affirmed back in 2009, and if it did hold others who were not students and were sent there by Abu Zubaydah, that seems to be because Zubaydah — who was not a member of Al-Qaeda, remember — was actually involved in moving all manner of people — men, women and children, civilians as well as soldiers — out of the war-torn chaos of Afghanistan, and had a connection with the “Issa House,” whereby occasional visitors stayed alongside the students.

I will discuss al-Sharbi’s case below, but first I want to look at the case of Ravil Mingazov (ISN 702), the Russian who was seized in another house in Faisalabad, the “Issa House,” that the US has tried — largely without success — to portray as a house associated with Al-Qaeda. It appears to have held many students who ended up in Guantánamo, as a US judge affirmed back in 2009, and if it did hold others who were not students and were sent there by Abu Zubaydah, that seems to be because Zubaydah — who was not a member of Al-Qaeda, remember — was actually involved in moving all manner of people — men, women and children, civilians as well as soldiers — out of the war-torn chaos of Afghanistan, and had a connection with the “Issa House,” whereby occasional visitors stayed alongside the students.

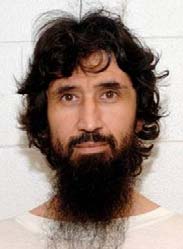

Ravil Mingazov appears to have been one of these men. An ethnic Tatar who had fled his homeland because of oppression, leaving his family, he seems to have drifted around Afghanistan and Pakistan, ending up in a Jamaat-al-Tablighi centre in Lahore, from where he took a ride with two other men to a place in Faisalabad where, they were told, those who needed passports to return home would find help. Taken first to Abu Zubaydah’s house, Shabaz Cottage, two of the three, including Mingazov, were then moved to the “Issa House,” where they were seized.

Most of the men seized in that house raid have now been freed (see here, for example, for the story of Fahmi Abdullah Ahmed, freed in January), but Mingazov is an exception, even though, back in May 2010, a judge ordered his release, having found that the government had failed to establish that he was connected to either Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. The government, however, appealed, and the case has, shamefully, not been dealt with in the six years since, leaving MIngazov in a disgraceful state of limbo. See my article from September 2011, The Black Hole of Guantánamo: The Sad Story of Ravil Mingazov, for further information.

Prior to his PRB, the US government presented its case against him in an unclassified summary that was noteworthy for failing to provide anything resembling evidence of any kind of wrongdoing against Mingazov — in particular in the line, “Due to his inability to communicate in any language other than Russian, he probably did not hold any positions of authority in Afghanistan.”

As the summary described it, Mingazov, an ethnic Tatar, “served in the Russian military as a logistics warrant officer from 1989-2000, when he resigned over what he characterized as the Russian Government’s treatment of Muslims.” Those coming the summary suggested that “[h]is feelings on this subject likely led him to seek out extremist groups.” He then allegedly joined the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and “trained in Tajikistan until early 2001, when the group was forced to leave and collectively traveled to Afghanistan.” By mid-2001, it was suggested, he “had probably joined the Tatar Jama’at group, which took a strong position against Russia’s policies towards Muslims.”

Following the one use of the word “probably” above, it was then suggested that, in mid-2001, he “probably attended several training camps in Afghanistan where he learned to make explosives, poisons, and chemical grenades.” It was also noted that he “has admitted to fighting with the Taliban against the Northern Alliance, but said he did not fight against Americans.”

This is the point at which the key line is delivered, revealing that he had no way of communicating with those in whose company he found himself: “Due to his inability to communicate in any language other than Russian, he probably did not hold any positions of authority in Afghanistan.”

He then reportedly “fled to Pakistan in January 2002,” where he stayed at a series of safe houses, described, of course, as “al-Qa’ida affiliated-safehouses,” and then made his way to Faisalabad, where he was seized.

Securing information about him has evidently proved difficult. The authorities claimed that, “[b]ased on information following his arrest, he was known to have some experience in dealing with different types of explosives,” but also conceded that “[w]e have no information from other detainees on [his] pre-detention activities.”

It was also noted that he “has been mostly compliant with the guard force at Guantánamo, with a relatively low number of infractions compared to other detainees, according to Joint Task Force-Guantánamo (JTF-GTMO) reporting.” However, according to the US authorities, “Despite being open with interviewers about his time in Russia, [he] has provided few and contradictory details about his time in Afghanistan and the circumstances that led to his arrest in an al-Qa’ida-affiliated safehouse” — although I tend to think that is untrue, as the story of how he ended up at the “Issa House” has been reported over the years in a variety of accounts by various prisoners involved, none of which tend to suggest that anything untoward was taking place.

The summary also noted that Mingazov “maintains a strong disdain for the Russian Government and does not want to be repatriated, claiming his treatment in Guantánamo is better than the treatment he received in Russia.” The summary continued, “He probably also fears facing criminal charges that the Russian Government has levied against him.”

The summary also noted that, if he were to be “transferred back to Russia and not charged with a crime,” he “would probably live with his mother in Tatarstan until he becomes self-sufficient, and then seek to leave Russia,” although it seems unlikely that this would be a viable option, given the Russian government’s oppressive treatment of all the other prisoners who returned from Guantánamo many years ago.

Rather confirming that return to Russia will not be possible, because of the manner in which the Russian authorities are likely to treat him, the summary concluded, “Although he does not have any direct connections to known terrorists at large, [his] attitude towards the Russian Government could lead him to seek out individuals with a similar mindset, and he has discussed returning to the fight against Russia.”

Below I’m cross-posting the opening statements made by Mingazov’s personal representative (a member of the US military appointed to help him prepare for his PRB), and by one of his attorneys, Gary Thompson of Reed Smith LLP in Washington, D.C. The representative spoke about how he has “developed close friendships at Guantánamo, due in large part to his calm, friendly demeanor,” and noted how he “desperately wants to re-connect with his only son, now a teenager,” who lives with his ex-wife and in the UK, where they successfully sought political asylum.

Thompson also spoke of his hopes that his client can be reunited with his family in the UK (see the Guardian‘s article about his case), and delivered the following defence of Mingazov’s character that I hope was of use to the board: “I believe and know Ravil to be a kind and peaceful man who, if released, will do no harm to anyone. He will live the rest of his days as a devout and peaceful Muslim, a loving father and family member, a good son to his mother (for her remaining days), a cheerful friend to all those around him, a physically and mentally healthy person, and a productive employee in any number of jobs that he would eagerly take.”

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 21 June 2016

Ravil Mingazov, ISN 702

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. As the Personal Representative for RaviI Mingazov (ISN 702), I would like to thank the Board for allowing me this opportunity to demonstrate how RaviI is no longer a continuing significant threat to the United States.

Ravil is a Russian Tartar [sic], a religious and ethnic minority group from the Tartarstan [sic] region of Russia. He grew up in a loving family and led an active life, ultimately becoming a professional-level ballet dancer prior to being conscripted into the Russian military like most young men. During his time in the Russian military, RaviI never trained for combat duty. Actually, his first two years of service were part of a military ballet troupe. Following this, he served in support roles performing passport control on the border with Mongolia and then managing all food, logistics, and cooking for a base of around fifteen hundred people.

During Ravil’s time in the Russian military, he became increasingly bothered that he was not allowed to observe basic tenets of the Islamic faith while on duty, such as pray[ing] or eat[ing] halal food. His attempt to peacefully engage military and civilian political leadership on this issue started a chain of events that eventually drove him to leave Russia and seek an Islamic country where he and his family could more freely practice their religion. While traveling from Russia to Tajikistan, his young son became very ill, so his wife was forced to return to Russia with their son to seek medical care. The Tajikistan government eventually relocated Ravil and many other foreigners out of the country, leading to his arrival in Afghanistan. RaviI never fit in with any group due to suspicion of his Russian background. He survived by performing menial tasks and moving often. Following the onset of coalition operations, he joined the waves of people fleeing Afghanistan, eventually crossing into Pakistan where he was detained at a guest house.

While at Guantánamo, Ravil has been a compliant detainee who has never taken part in any non-religious fasting, even when most other detainees participated. RaviI took numerous classes in Life Skills, Arabic, and Arabic to English. Despite the language barrier with other detainees, Ravil developed close friendships at Guantánamo, due in large part to his calm, friendly demeanor. RaviI desperately wants to re-connect with his only son, now a teenager with no memory of his father prior to detention. Ravil’s son, ex-wife and other in-laws currently live in the United Kingdom under political asylum and have written numerous letters pledging to support Ravi! upon his release. Ravil holds no grudges against the United States and, in fact, greatly admires the religious freedom that America offers. RaviI is prepared to answer all of your questions truthfully and respectfully in order to demonstrate he is not a continuing significant threat to the United States. Thank you.

Periodic Review Board

Initial Hearing of June 21 2016

Statement by Gary Thompson

Personal Counsel for Ravil Mingazov (ISN 702)

Dear Members of the Periodic Review Board:

Thank you for accepting this statement from me as Personal Counsel (PC) in this PRB hearing for Guantánamo detainee Ravil Mingazov. I am a private, pro bono attorney from the law firm of Reed Smith LLP in Washington, D.C. (where I serve as the D.C. office managing partner). I have been practicing law for 26 years, always with time for pro bono cases of many kinds. In 2005, my firm accepted several detainee representations for their respective habeas corpus cases. At the time, a former Marine officer (Doug Spaulding) and Army officer (Bernie Casey) took the cases and I was pleased to join them. Since 2007, I have traveled to Guantánamo many times and spent many days meeting with Ravil. With Doug and Bernie now retired, I have become the lead counsel, including as PC in this hearing.

I fully understand and appreciate the issue being considered by this panel – whether RaviI, if released, would be a “threat” to anyone (taking into account security measures by the receiving country). My background allowing me to comment on this matter includes my in-person meetings with RaviI over the last 10 years, letters exchanged, and also calls, Skype, and letters exchanged with Ravil’s mother, former wife, and son. I am also very familiar with all of the evidence concerning Ravil, including as presented in his habeas case (presently still active, on appeal by the government), although of course I do not comment herein on any of that evidence or allegations.

Please appreciate that I have thought and reflected long and hard on the issue over the course of many years, and most recently, during my usual ultra-long-distance runs. This is my considered conclusion: I believe and know Ravil to be a kind and peaceful man who, if released, will do no harm to anyone. He will live the rest of his days as a devout and peaceful Muslim, a loving father and family member, a good son to his mother (for her remaining days), a cheerful friend to all those around him, a physically and mentally healthy person, and a productive employee in any number of jobs that he would eagerly take.

Ravil’s son and other family members now residing in Nottingham, England would receive Ravil with open arms (assuming, we hope, the United Kingdom sees fit to accept an asylum petition). They will give him a bed and use of an apartment, feed him, care for him, help him transition, and help him find gainful employment. The United Kingdom, of course, would provide the highest levels of security assurances.

With respect to Ravi! and his peacefulness, I have come to these conclusions because I have observed his character over many years. Ravil has always greeted us, first and foremost, as his friends. He has never been impatient or hostile with us personally in any way. On the contrary, almost without exception, Ravi! has been kind, cheerful, and humorous — something that is extraordinary to us given his long imprisonment. More, I have never heard Ravil lash out or say anything negative or threatening about anyone — not about any guard, officer, fellow detainee, any American leader, or anyone. When discussing Russian politics, Ravil does so with a keen and deep understanding of the issues, history, and a respect for the struggles of ethnic people who simply want to live and worship in peace. We have spent much time in excellent conversation about history, leaders, philosophy, literature, and other topics. And we also talk at great length about our families, friends, and the simple things of life — the interesting animals and creatures of Guantánamo, the pleasant weather, our mutual like of running and exercising, and our hopes and dreams for the future.

For sure, over the years, we have reviewed, and re-reviewed, every last detail about his past, his whereabouts in 2000-2002, the conditions at GTMO, and the endless labyrinth of his never-ending habeas case in court. Discussing the court case gets tedious, and so we mostly simply talk as friends, increasingly so as the years go by. This is also the case with our longtime translator and all the other counsel Ravil has befriended over the years (especially Doug Spaulding, who has spent the most time with Ravil). So it is not surprising that so many people — family, friends, counsel, fellow detainees — have taken the time to write such positive statements about Ravi!. I hope that these statements taken as a whole, along with Ravil’s statement, will convince you that the PRB clearance standard in this case is very well satisfied.

l plan to be present at the June 21, 2016 PRB hearing, where I would be pleased to discuss these issues further, including any questions that the Panel may have regarding the classified summary.

Ghassan al-Sharbi’s Periodic Review Board

Two days after Ravil Mingazov’s PRB, Ghassan al-Sharbi’s case was also considered by the board, although, as noted above, he was not present, and as a result it is certain that he will not be approved for release. He did to even meet with his personal representative, who was able only to state, “Mr. Sharbi has not attended any scheduled meeting and therefore, I am unable to describe my first-hand knowledge of him.”

Writing about him back in October 2010, I stated:

Al-Sharbi, who speaks fluent English and graduated in electrical engineering from Embry Riddle Aeronautical University in Arizona, is one of very few Guantánamo prisoners to have publicly declared membership of al-Qaeda. In his tribunal at Guantánamo, he accepted all the allegations against him, which included claims that he received specialized training in the manufacture and use of remote-controlled explosive devices to detonate bombs against Afghan and US forces, that he “was observed chatting and laughing like pals with Osama bin Laden,” and that he was known in Guantánamo as the “electronic builder” and “Abu Zubaydah’s right-hand man.”

Charged in the first incarnation of the Military Commissions, he appeared at a pre-trial hearing on April 27, 2006, and was equally open about his activities, telling the judge, “I came here to tell you I did what I did and I’m willing to pay the price,” “Even if I spend hundreds of years in jail, that would be a matter of honor to me,” and “I fought the United States, I’m going to make it short and easy for you guys: I’m proud of what I did.”

Perhaps surprisingly, al-Sharbi, who was a member of the short-lived Prisoners’ Council in the summer of 2005, along with Shaker Aamer (ISN 239) and four others who have been released, was befriended by Guantánamo’s warden, Col. Mike Bumgarner, despite his avowed allegiance to al-Qaeda, and despite the fact that he later became one of Guantánamo’s most persistent hunger strikers.

In June 2008, he was again put forward for a trial by Military Commission, along with Sufyian Barhoumi, Jabran al-Qahtani and Noor Uthman Muhammed (see below), but the charges were dropped by the Pentagon in October 2008, after their prosecutor, Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld, resigned, stating that the trial system was designed to prevent the disclosure of evidence essential to the defense. New charges against all four men were filed in January 2009, in the dying days of the Bush administration, but with the exception of Noor Uthman Muhammed, have not been revived under President Obama, perhaps because, as in the majority of cases involving Abu Zubaydah, the government has stepped back from its discredited claims about his significance.

I later met his military defense lawyer, now retired, and his sister, who assured me that he was not a threat to the US, but whether or not this is true, al-Sharbi has done nothing to persuade the authorities that it would be safe to free him, and, on this point, his refusal to engage with the PRB is a disaster.

For what it’s worth, the government’s unclassified summary painted a picture of him that would seem to ensure that he will have to work very hard at persuading the US authorities to release him if he ever wants to be a free man again.

The US authorities stated that he “attended a US flight school where he associated with two 9/11 hijackers, constructed electric circuitry in Pakistan for improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to attack Coalition Forces, and may have been involved in Homeland attack planning after 9/11.”

“From 1999 to 2000,” the summary continued, “he attended Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott, Arizona and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Avionic Electrical Engineering. [He] traveled to Afghanistan in the summer of 2001 and trained at the al-Farouq camp. After 9/11, [he] traveled to Pakistan and was selected by a senior al-Qa’ida military commander to receive training on how to manufacture radio-remote controlled IEDs (RCIEDs) with the intent of training other extremists in bomb-making techniques.”

The summary also claimed that, ‘[w]hile in Pakistan, he also attended meetings with al-Qa’ida leaders where they may have discussed attacks against the US, possibly including the plot by Jose Padilla to explode a radiological ‘dirty-bomb.’” However, the big problem with this claim is that Padilla, held and tortured as an “enemy combatant” on the US mainland, and then punitively sentenced for a few phone calls, had never been involved in a “dirty-bomb plot.” As I explained in an article in October 2008:

Speaking in June 2002 [just after Padilla’s capture], Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy to US defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, admitted that “there was not an actual plan” to set off a radioactive device in America, that Padilla had not begun trying to acquire materials, and that intelligence officials had stated that his research had not gone beyond surfing the internet.

Turning to al-Sharbi’s behavior in Guantánamo, the summary noted that he “has been mostly non-compliant and hostile with the guards throughout his detention,” and has made “conflicting statements” about “the extent of his affiliation with al-Qa’ida and the training he received.” The summary added, however, that “his behavior and statements indicate that he retains extremist views and believes that quitting jihad is wrong.” He also, it was noted, “espouses a strong dislike for the US and has said that he wants to remain in Guantánamo to continue his jihad against the US military and US Middle East policies,” and “has told interrogators that he will reengage in terrorist activity against the US to defend lslam from the presence of US military forces in Saudi Arabia, and that the US got what it deserved from the terrorist attacks on 9/11.”

Commenting on what would happen if he were to be released, the summary noted that his “electrical engineering degree and a petroleum and minerals degree from King Fahd University. Saudi Arabia, could provide him with a skill set for employment if he is released,” but the summary’s authors added that, “based on his education and training, we believe [he] is also a technically proficient and skilled bomb maker whose electronics expertise would place him in high demand by extremist organizations, and his past relationship with extremists would provide [him] a path to reengage if he chose to do so.”

It was also noted that, “In addition to refusing to speak with interrogators, [al-Sharbi] refuses to meet with lawyers and foreign delegations regarding his detention hearings and possible transfer, which limits our ability to fully evaluate his future intentions and motivations. Should [he] return to Saudi Arabia, we assess that he would seek support from family members, although we lack insight into the extent to which they would be able to support him financially upon his return.”

Abd al-Salam al-Hilah’s request to be freed is turned down

On June 22, the day between the two PRBs discussed above, a review board turned down a request by Abd al-Salam al-Hilah (aka al-Hela) to be freed, which I wrote about in an article entitled, Yemeni Tribal Chief, Businessman, Intelligence Officer and Torture Victim Seeks Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Board.

Despite his high-profile status in Yemen, the board, in its final determination, stated that, by consensus, they had “determined that continued law of war detention of the detainee remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

The board members stated that they had “considered [his] extensive and prolonged facilitation of extremist travel, his failure to acknowledge or accept responsibility for past activities, and his deceptive and non-responsive answers to the Board’s questions.” They added that they will welcome seeing his file in six months, and that they hope he will deal “with greater candor about his ties and roles in facilitating extremist activities, so that the Board can better understand his past and current intentions.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.