Please support my work!

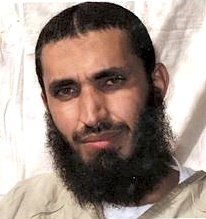

Last week, in a decision that I believe can only be regarded objectively as a travesty of justice, a Periodic Review Board (PRB) at Guantánamo — consisting of representatives of six government departments and intelligence agencies — recommended that a Yemeni prisoner, Abdel Malik al-Rahabi (aka Abd al-Malik al-Rahabi), should continue to be held. The board concluded that his ongoing imprisonment “remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

In contrast, this is how al-Rahabi began his statement to the PRB on January 28:

My family and I deeply thank the board for taking a new look at my case. I feel hope and trust in the system. It’s hard to keep up hope for the future after twelve years. But what you are doing gives me new hope. I also thank my personal representatives and my private counsel, and I thank President Obama. I will summarize my written statement since it has already been submitted to the board.

I have been compliant in the camp facilities and other detainees trust me. I have taken the opportunities for education and personal growth. I have been preparing myself for the life after Guantánamo.

When I return to Yemen, I want to resume my education. My father, who is a tailor, has a job for me in his shop. I have a wife who longs for me and 13-year-old daughter who badly needs me. She’s a light — she is the light of my life.

Being apart from Ayesha has been the hardest part of my detention. In our calls, she says I want you to take me to the park; I want you to help me with my homework. She sends me five or six letters at a time. I will never again leave Ayesha without her father, my wife without her husband, my parents without their son. I want to make up for the twelve years I have been away.

The PRBs were first proposed in March 2011, when President Obama issued an executive order authorizing the ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial of 48 Guantánamo prisoners. These men had been recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009, on the dubious basis that they were too dangerous to release, but that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

Disgracefully, although President Obama promised regular reviews for these men when he issued the executive order, it took over two and a half years for the first PRB to be convened. In the meantime, two of the 48 men had died, but 25 others — originally designated for prosecution by the task force — were added to the PRB list, making 71 men in total.

The first PRB, in October, led to a recommendation that the prisoner in question, Mahmoud al-Mujahid, a Yemeni, should be released — although the irony, of course, is that he merely joined 55 of his compatriots, who were cleared for release by the task force in January 2010, but are still held because of unreasonable fears about the security situation in Yemen.

In al-Rahabi’s case, although the Board “took into consideration [his] strong family support awaiting his return, including housing, employment opportunities, and a wife and daughter ready to support him,” they worried about other alleged problems — described as his “significant ties to al-Qa’ida, including his past role as a bodyguard for Usama Bin Ladin [sic] and a prior relationship with the current amir of al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula.” The board added, “Further, his experience fighting on the frontlines, possible selection for a hijacking plot, and significant training raise concern for the Board,” and also stated, “The detainee’s planned return to Ibb, assessed to have a marginal security environment, and ties to a relative who is a possible extremist, raises concerns about his susceptibility to reengagement.”

This would indeed be a worry, if any of it was true. Unfortunately, however, it has never been established objectively that there is any truth to the allegations. The most significant claim is that al-Rahabi was a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden, part of a group of men described as the “Dirty 30″ — all alleged bin Laden bodyguards, captured crossing the border from Afghanistan to Pakistan in December 2001.

See if you think this is plausible: al-Rahabi, who was born in 1979, would have been just 22 years old when he was seized. Is it really likely that, having arrived in Afghanistan in the summer of 2000, this young man rose to become a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden in such a short amount of time? In his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, witnesses queued up to accuse him, but all are suspicious — Sanad al-Kazimi, Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj, Ahmed al-Darbi, Mohammed al-Qahtani, Hassan bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi (a “high-value detainee”), who were all tortured, and Yasim Basardah, the most notorious liar at Guantánamo.

Moreover, the “high-value detainee” Walid bin Attash claimed that al-Rahabi was “a designated suicide operative,” who, in 1999, “trained for an aborted al-Qaida operation in Southeast Asia to hijack US airliners and crash them into US military facilities in Asia in coordination with 11 September 2001,” for which all the planned operatives swore bayat (an oath of allegiance) to Osama bin Laden. However, there is no evidence that al-Rahabi was in Afghanistan in 1999.

Even more ridiculous is a claim by Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi (Ali Muhammad Abdul Aziz al-Fakhri), the leader of the independent Khaldan training camp, who was held in a variety of CIA “black sites” before being returned to Libya under Colonel Gaddafi, where he died in prison under suspicious circumstances in 2009. Al-Libi reported that al-Rahabi arrived in Afghanistan in 1995, when he was just 16, staying until 1996.

It may be that these allegations are more trustworthy than my analysis suggests, but I doubt it, as they are typical of prisoners who were tortured, or, in Yasim Basardah’s case, provided false allegations against a shockingly large number of his fellow prisoners to improve his own living conditions at Guantánamo, prior to his release in 2010.

The fact that, over 12 years after his arrival at Guantánamo, al-Rahabi is still being judged as “a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” based on information that has never been subjected to any kind of objective scrutiny, is thoroughly unjust, and shows how little regard for the truth the Obama administration and the Periodic Review Board members have — or, to put it another way, how much regard they have for the hugely unreliable collection of lies and hearsay masquerading as evidence in the files on the prisoners put together at Guantánamo.

Al-Rahabi’s case will apparently be considered again in six months, when I hope the board takes a less credulous approach to his perceived dangerousness, but I doubt this will happen, as there seems to be no impetus for the board, or the administration in general, to take a realistic view of the prisoners, rather than one full of distortion, innuendo and outright lies.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.